- Home

- Media Kit

- MediaJet

- Current Issue

- Past Issues

- Ad Specs-Submission

- Reprints (PDF)

- Photo Specifications (PDF)

- Contact Us

- PRIVACY POLICY

- TERMS OF USE

![]()

ONLINE

![]()

ONLINE

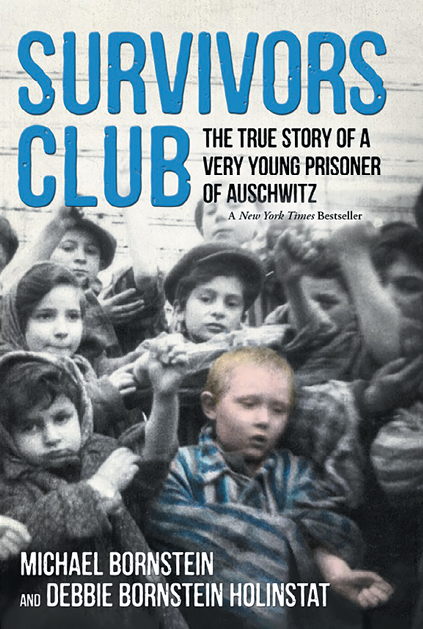

Survivors Club

Editors’ Note

Michael Bornstein survived for seven months inside Auschwitz, where the average lifespan of a child was just two weeks. Six years after his liberation, he immigrated to the United States. Bornstein graduated from Fordham University, earned his PhD from the University of Iowa, and worked in pharmaceutical research and development for more than 40 years. Now retired, he lives with his wife in New York City and speaks frequently to schools and other groups about his experiences in the Holocaust. With Debbie Bornstein Holinstat, he is the author of Survivors Club: The True Story of a Very Young Prisoner of Auschwitz.

Will you discuss your life journey?

I was born in Zarki, Poland on May 2, 1940. It was already being turned into a ghetto at that point and conditions were very hard for my family. I had a big brother, Samuel, my dad, Israel Bornstein, and my mom, Sophie. My father was selected to be president of the Judenrat in my community. That was sort of a liaison between the Nazis and the Jewish people. He was able to use that position to the benefit of all the Jews in Zarki, sneaking travel visas to hundreds of people so they could try to escape Poland and stepping in when harsh punishments were levied on neighbors. Unfortunately, though, every Jew in Zarki was “liquidated” in 1942 and in 1943, forced onto trains to work camps or death camps. At first, my family was taken to the Pionki Labor Camp. In July 1944, Pionki was liquidated. My mom, dad, brother, grandmother Dora and I were all herded into a cattle car and taken to Auschwitz.

I was only four years old, so my memories of that trip are very fuzzy. For some reason, I remember the smell that hit me when we arrived at Auschwitz. I later learned that foul, disgusting smell was the smell of burning bodies. I still remember Nazis screaming at me in German, but I didn’t understand German. My father and 10-year old brother were taken to the men’s side of camp. My mother and grandmother were put in a women’s bunk in Auschwitz-Birkenau. And although most young children were killed almost immediately at Auschwitz-Birkenau in 1944, I was miraculously placed in a children’s bunk and my arm was tattooed with B-1148. I was one of the youngest and smallest, and the older children would steal my bread rations out of desperation. My mom, Sophie, risked her life to sneak into the children’s bunk to share stolen pieces of food with me. Eventually, she smuggled me out of the children’s bunk and kept me hidden in the women’s bunk, risking her life again to keep me safe. When my mother was selected to be deported out of Auschwitz to an Austrian labor camp, she had to leave me behind in hiding. My grandmother, and all those strangers living in the women’s bunk – they kept me safe. I hid under piles of straw during the day so I wouldn’t be caught.

.png)

Michael Bornstein (right) with other children at

the Auschwtiz concentration camp

In early 1945, I became ill. I was so sick that my grandmother snuck me to the infirmary at Auschwitz-Birkenau to get me help. That decision saved our lives. In January 1945, as Allied Forces got closer to liberating Auschwitz, the SS soldiers organized a Death March. They marched tens of thousands of prisoners through the woods in the cold, but they didn’t clear out the infirmary. Soviet soldiers liberated my camp on January 27, 1945. I was finally free.

My grandmother, Dora, took me back to Zarki. However, life remained difficult. Local Polish people had occupied our home and refused to let us in. I was very sick with typhoid fever, and we had very little clothes or food. We lived through the winter in a chicken coop with mesh walls and a board for a roof. Eventually, someone who looked vaguely familiar came to the coop to find me. It was my mom Sophie, who had also survived. Incredibly, all six of her brothers and sisters also survived their own traumatic experiences. There was a lot to celebrate, but a lot to mourn. My father, Israel, and my older brother, Samuel, were murdered in the gas chambers at Auschwitz. My mother and I had to rebuild without them. In 1951, we got Visas to come to the U.S. I studied hard, earned scholarships, got my pharmacy degree from Fordham University and my PhD in Pharmaceutics and Analytical Chemistry from the University of Iowa. I spent my career researching life-changing medications, but my greatest accomplishment and source of pride is my family. My wife, Judy, and I have four children and twelve incredible grandchildren. I feel very lucky.

Michael Bornstein being carried by his grandmother Dora

You recently returned to Poland on the 80th anniversary of the liberation of the German Nazi concentration camp Auschwitz. What was this experience like for you?

It was a difficult trip. To be honest, I didn’t really want to go back there. What really changed my mind was hearing that my kids and grandkids would join me on the journey. All four of my children and 7 of my 12 grandkids were able to travel with me to Poland so that I could show them their history. It was the most meaningful memory for all of us. My grandkids held my hand and supported me, even though many of them were breaking down with emotion themselves. It is so hard to stand in that place where more than a million Jewish people were murdered, just because of their religion. We walked into a crematorium where bodies were burned, including my brother and my father. You can’t help but feel like, “How could the world have let this happen?” It was particularly difficult because at this time the world is experiencing unbelievable levels of antisemitism which we haven’t witnessed since the Holocaust.

How meaningful was it to have your family with you on this trip?

The truth is, I wouldn’t have traveled back to Auschwitz for the 80th anniversary of my liberation if it wasn’t for my family’s encouragement. If they weren’t coming along, I wasn’t going. I figured this may be my last chance to stand in that place and show my grandchildren what happened to me and to their great-grandparents and great-uncle. It’s so important that they know and that they remember, because it’s really their obligation to make sure the next generation doesn’t forget. I’m not going to be around forever, and I’m afraid Holocaust history is already being distorted. Several of the grandkids had to miss important classes to make the really long trip, but they did it for me and for the sake of remembrance. They’re incredible – and I’m not biased at all.

Michael Bornstein with his family at the 80th anniversary

of the liberation of the Auschwitz concentration camp

What interested you in writing the book, Survivors Club, and what made you feel it was the right time for the book?

My daughter, Debbie, is a writer and she asked me for many years to help write Survivors Club, but I always said “no ” I thought the best way to stay positive was to just look forward and try to forget my childhood completely. Two things changed my mind. As my grandkids started getting older and asked questions, I realized I wanted my story down on paper for them. It required a lot of research, because there are pieces of my own history I don’t know. I was so young that my own memories are very limited. Researching and writing Survivors Club felt critical at this moment in time when polling shows that about half of millennials and Gen Z can’t name a single concentration camp. Most don’t even realize that six million Jews were killed in the Holocaust.

The other thing that motivated me to write Survivors Club was denialism. Holocaust deniers are getting louder, and I can’t let that be the last voice people hear. I’m still here on this earth, and people are saying the Holocaust never happened. What will happen if every last living survivor doesn’t step up to tell his or her story?

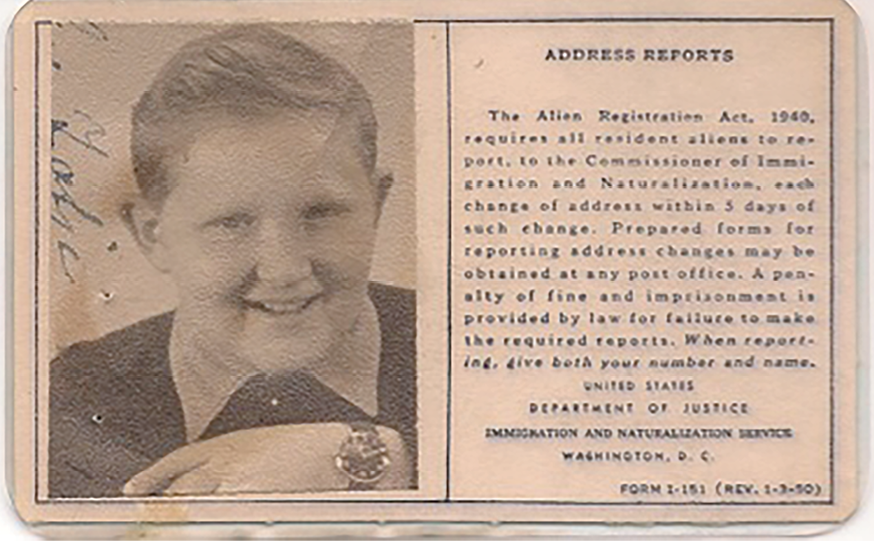

A bald Michael Bornstein after the war

What are the key messages that you wanted to convey in the book?

The most important message I wanted to convey was a reminder that everyone needs to stand up against injustices they see around them, even if it doesn’t affect them. The Holocaust didn’t start with burning bodies. It started with small indignities, jokes about Jewish people, vandalism of property and harassment. It happened so quickly – those sparks of hatred turned into a raging fire of genocide. No one stood up against it, until it was too late.

Your son, Scott Bornstein, is the Executive Vice President of international law firm Greenberg Traurig. He has used his position as a law firm leader to bring actions against organizations and individuals who are promulgating antisemitism in the U.S. and on college campuses. How does that make you feel?

I’m so proud of Scott. I was only four years old when I was taken to Auschwitz. My father and brother were killed. I couldn’t fight back. Scott made the choice to use his talent and his position to stand up against antisemitism and bigotry. The easy thing for him to do would have been to continue to be a leader at his law firm and to solely focus on servicing his clients, but instead he has donated hundreds of hours of his time with incredible support from Greenberg Traurig to battle antisemitism. The lawsuits he has brought will, no doubt, help eliminate the scourge of bigotry and Jew-hatred that seeped their way onto college campuses when no one was paying attention. I have twelve grandchildren and about half of them are college-age. I never imagined they would feel the kind of antisemitism that existed in Europe in my generation. And yet, here we are. Scott’s work is one example of the kind of action that’s called for in this dangerous moment in time. I’m extremely grateful that all four of my kids and twelve grandkids are proud of their heritage and they bravely use their voices to stand up against hate and intolerance in all forms.

Michael Bornstein’s U.S. Department of Justice displaced person card

What more can be done to address the issue of antisemitism?

To me, the answer is education. In Germany today, every single school student must learn about the Holocaust and even visit a camp. Holocaust education is a government mandate. I wish we made the same kind of promise here in America. The Holocaust was the worst genocide the world has ever seen. If you remind young people how bad things can get, how devastating unchecked bigotry can be, then maybe you encourage kids to stand up sooner – so a Holocaust can never happen again. I’d like to see a federal mandate for Holocaust education. As part of that educational process, I also think it’s critical to teach young people about all the amazing positive contributions that Jewish people have made over the years to healthcare, the arts, business, technology and much more. It’s important to emphasize that we are not merely victims. We are strong, intelligent, creative people who have given back so much to society. I also think something has to be done about the spread of misinformation on social media. In the wake of the October 7th terror attack in Israel, the world turned on Israel almost immediately. I think social media disinformation had a lot to do with that. I would also like to see universities do a much better job protecting the rights of Jewish students. No child should be fearful to attend college simply because of their religious beliefs or ethinicity. Despite all of this, I remain optimistic that good will prevail over evil.![]()